It's a story so little known yet so fascinating that our children should be learning it in schools... The W+B Magazine lets you discover how the Walloons contributed to saving Swedish industry in the 17th century.

In the 17th century, Sweden called on foreigners to help it find a way out of the industrial slump the country found itself in. And we're not talking about the French nor the English. No. These foreigners arriving in this Scandinavian land come from a small region, not yet part of Belgium: Wallonia. Why Wallonia? Because this region boasts an expertise in metallurgy like nowhere else. So good it's worth devoting a whole feature to it.

Context

To understand how the Walloons ended up in Sweden, we need to go back in time... No black and white here, photography didn't even exist yet. In the 17th century, images of daily life were largely depicted in painting. And here, the picture looks bleak. Europe was experiencing several wars that were to profoundly alter its economic structure: some countries found themselves plunged into misery, while others grew richer... This was the case for Wallonia, for a long time the continent's leading arms manufacturer, whose goods were transported via Amsterdam, the central hub of European trade. So it's hardly surprising that the King of Sweden took an interest when signing a peace treaty with Denmark in 1613. In Amsterdam, he's able to borrow money and offer his country's iron ore mines as collateral, even if the mines are not yet being operated as well as they could be. This situation gave a handful of inspired Walloon men an idea, and they would not only go on to make a fortune, but change the course of Swedish life for good.

The astonishing story of a Walloon in Sweden

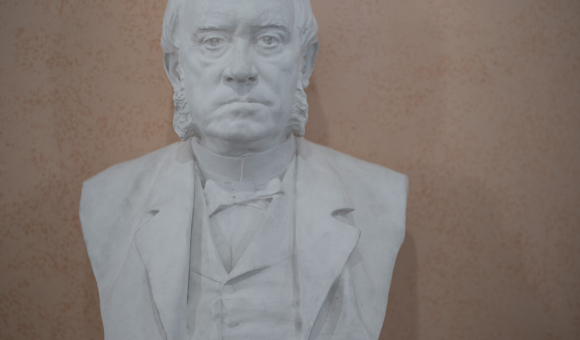

It may sound like a Belgian joke... but what the Walloons did in this Scandinavian country four centuries ago should be taken seriously. This is no mere anecdote in Swedish history, but a chapter of immense significance. For the Walloons' arrival in Sweden marked a clear turning point. And among them was a certain Louis de Geer. Born in the "Fiery City" of Liège in 1587, this businessman moved to Amsterdam, where he meets the de Besche brothers, who were already operating the Swedish ironworks of Nyköping and Finspang. This initial contact would lead on to many more, as Louis de Geer quickly realises that there are interesting business opportunities to be had there. He establishes himself as King Gustavus Adolphus' cashier in Amsterdam, and thanks to his astonishing rate of production, becomes the main supplier of military equipment and artillery to the Swedish army. De Geer therefore finds himself juggling two different roles before the Thirty Years' War, from 1618 to 1648, brings about a radical change to the course of his life — a godsend for him! He joins the de Besche family in Sweden to set up a military arsenal. But he doesn't make the journey alone. With him, he brings along Walloon workers specialised in blast furnaces, refineries and foundries, to share the metallurgical techniques from Liège and Hennuyères. This turns out to be a huge success, and not without reason: at the time, the Walloons were the only ones to have succeeded in building a very large, heavy-duty blast furnace. They also use a new type of millstone in which the positioning of the logs produces charcoal that yields higher-quality iron. All these assets combine to make Louis de Geer an influential figure. And not just in Stockholm... The town of Norrköping essentially becomes his headquarters, also making it the hub of immigration and industry. But he's always on the look out for more. He buys a lot of land and, in 1627, becomes a Swedish citizen to settle his claims against the State. Thirteen years later, he's admitted to the ranks of the nobility. A meteoric rise, the likes of which no one could surpass. De Geer is now richer than any Swede has ever been. And it's not for nothing that he's still known as the father of Swedish industry today. Louis de Geer died in Amsterdam in 1652 at the age of sixty-five.

Profile of Walloon workers

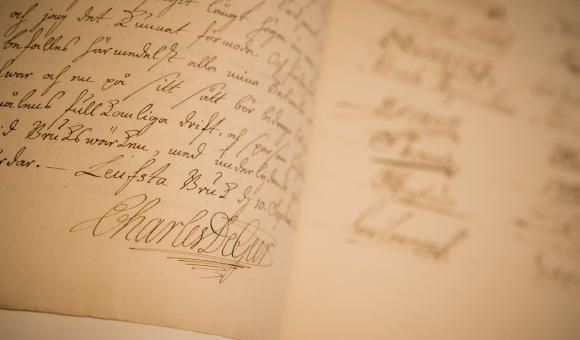

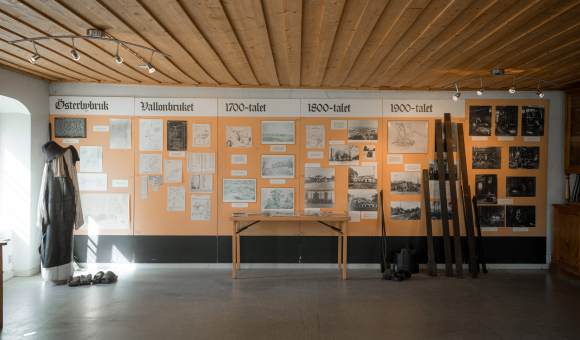

Despite their skill in the trade, many people were unemployed in Wallonia. So, to escape a critical situation, exile quickly became the solution — and a "mass" exile means organisation. Recruiting offices were set up to enable recruits (who were often illiterate) to sign contracts before a notary, with the contracts lasting one to two years. Benefits include a free return trip for the worker, and for his family if they decide to accompany him. The condition is that they must stay within their assigned ironworking community. Once everything has been agreed, they head for Norrköping, then Finspang and the ironworks of Uppland. Here, families receive either a plot of land on which to build a house, or a dwelling that forms part of a community building. Everyone's in it together. Contact with the Swedes is rare, as trade secrets must be protected at all costs. So, Walloon continues to be spoken thousands of kilometres away from Wallonia. And this goes on for generations. It was only much later, when foundries and ironworks gradually opened up to the Swedes, that they started to pick up foreign expressions from afar. It's a story worthy of a film — just as captivating whether in black and white or colour! Fortunately, the lack of images doesn't hinder our imagination. Thanks to the archives, we can really get to know our ancestors, discovering their debts, their habits and, why not their dreams too? The ultimate aim for young boys was to become master blacksmiths. Now that's awesome; you earn a decent salary, you're the king of all workers. It should be said that this community life centred around the ironworks includes many different trades: charcoal burners and blacksmiths, of course, but also many craftsmen, masons, carpenters, shoemakers and even millers. And then there are the secretaries, accountants, gardeners and servants, for the forge master needs people to maintain and run the manor that he and his family lives in. Everything is highly codified and organised. Everyone has their place, and there's a place for everyone. Women are not just for staying at home — they have to be useful, work hard, perform "feminine" tasks as well as helping their husbands in the fields, in the mines... They do the "dirty" work. They grind the ore before transporting it on heavy boats. They're working on all fronts. An unenviable fate, but one nevertheless accepted by many. In those days, it was better to live in the shelter of the ironworks than outside, where witchcraft trials were rife...

A duty of remembrance

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Wallonia was the centre of Europe's steel industry. Ironworks and blast furnaces were in constant operation. But sadly, few traces remain today. A result of the many wars fought on the territory: over six hundred between 1500 and 1832, when Belgium had just been founded. And then, gradually, the sector declined... It was a terrible crisis, with unemployment ravaging our region. And in the 1970s, coal mines and steelworks started closing down for good, one after the other. Maybe this explains why Belgians have forgotten that there is something good, something beautiful in this industrial history of Wallonia and Sweden. Memory is selective... But with a little willpower and enthusiasm, it can be revived.

Walloon ironworks — what actually are they?

The process for transforming cast iron into wrought iron was invented in the Liège region and exported to Sweden in the early 17th century, where it quickly became widespread. At the time, there were five Walloon ironworks operating with a charcoal blast furnace. Manganese-rich iron ore was used, like that from nearby Dannemora, which may explain the high purity of the wrought iron obtained after the piece of cast iron, weighing around 30 kilos, had been decarburised. That's how daring the Walloons were... They worked in shifts, forming teams of three or four, from Sunday evening to Saturday morning, 24 hours a day. The last thing they wanted was for the blast furnace to cool down or for production to come to a standstill.

Social and cultural anthropology of Walloon immigrants

If we think of Sweden's social and educational model as being today's shining example, it's mainly thanks to Walloon immigrants. Honestly. Here's three points to prove it.

- In the closed-off world of the ironworks, the inhabitants enjoy a level of security not seen anywhere else. For women, especially widows, this means a survivors' allowance. Children also receive a cereal allowance and schooling up to the age of twelve. As for the men, they're guaranteed work for life, and they still receive their wages even when they're ill. Another plus is the way the work is organised. When age becomes a problem, workers are permitted to switch to a less strenuous task, or to receive an old-age allowance to cover the bare essentials. And that's not all: if someone is no longer able to live on their own, they're moved to the infirmary, which then serves as a retirement home.

- There was no freedom of religion in Lutheran Sweden, but the Walloons are able to continue practising their religion (Calvinism) thanks to the pastors arriving with them — something never seen before!

- Unlike Swedish farmers, Walloon immigrants are very particular about cleanliness. Women take care of their bathrooms and inside their houses. As for the blacksmiths, their Saturday bath is a ritual so closely followed that it has become legendary.

Plus... it's impossible not to mention the Walloons' cultural contribution! At the time, they came from a society that was more advanced and wealthier than that in Sweden. They dressed well, they respected the regulations and, in the province of Uppland, they sang and danced too. A lot. They even developed folk music. The instrument of choice was the hurdy-gurdy, played with keys and a wheel turned by a crank. But the instrument ended up being burnt in the 19th century, as Puritans saw the festivities as a threat to morality. In the meantime, the Walloons' way of life in their ironworking communities had already changed certain aspects of society. Such is the case with Christmas and the feast of Saint-Jean, or the summer solstice, which are still celebrated today. Even the carnival, brought over from Belgium and still celebrated in the Walloon village of Gimo, on 13 January every year.

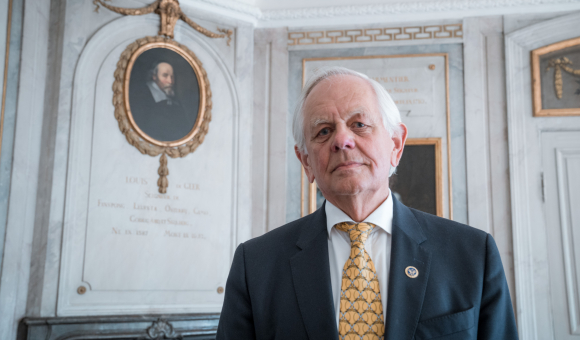

Unbelievable but true ! Louis de Geer is still alive today !

Four centuries have passed since Louis de Geer arrived in Sweden. And yet, he's still there. Valiant. A smile on his face. An image every bit as good as the painting of his ancestor in the family manor. For the Louis de Geer before us is the thirteenth of his name. It's a heritage he's proud of and protects as best he can. At the end of the seventies, business was going badly; they were on the verge of bankruptcy. So in 1986, he decided to set up a foundation to sustain the memory of his family and raise funds to maintain the estate. The result is clear: Louis de Geer succeeded in saving his heritage. And that's priceless. "My Walloon ancestor is considered the father of Swedish industry. You have to be worthy of it... Although that's not the aspect of it that I like the most. I'm more touched by the fact that it enabled many people to work, and therefore to survive. We don't have exact figures, but I think it's close to fifty thousand people in all." He says this without smiling; as if his mind were on something else. So we ask him how he feels about it all. There he is, sitting in the living room of the house in which he was born. Photos on a console table tell of a world that has now been swallowed up. We find ourselves imagining the habits of the various people that have inhabited this same place. Their discussions. Their moments shared around the table... "It certainly wasn't an easy decision to donate the house to a foundation. But I don't regret it. Today, it acts as a museum. I am at peace." Is this the final word? Not really. Louis de Geer likes to surprise. And his life story proves it. From boarding school, he moved on to the army, then to university, where he earned a degree in economics. He then moved to the United States, where he took a course in marketing before working for various companies. The story started off well... In fact, he was in charge of exports when his father died at the age of fifty-nine. A loss that prompted him to make a change in his life; attending agricultural school and buying a farm. Finding the earth as the ultimate refuge. Louis de Geer has now been a farmer for thirty-four years and is proud to be so.

Focus on the Society of Swedish Walloon Descendants

Founded in 1938 to honour the ancestral friendship between Wallonia and Sweden, the Society's aim is "to spread knowledge about the contributions of Walloons to Sweden's economic and cultural life" and "to bring together the descendants of Walloons who emigrated to Sweden in the 17th century, to contribute to the preservation of Walloon culture in Sweden and to create lasting contact with the population of Wallonia, its authorities and institutions". All these missions earned its president, Anders Herou, a knighthood in the Walloon Order of Merit in 2016.

Why are the Walloons so unaware of this Swedish story?

That is THE question. And so far, no one has the answer. Not even Amandine Pekel, Economic and Commercial Counsellor for AWEX at the Belgian Embassy in Stockholm for the past five years. It's enough to make her want to talk about it. Everywhere. All the time. And put an end to this strange anomaly. This question necessitated stopover in her office, along with a coffee and a smile, the key ingredients for a successful "fika" (a Swedish tradition of taking a break during the day).

Do you remember the first time you heard about the Walloons of Sweden?

Yes, it was my predecessor, David Thonon, who told me about it when I arrived here five years ago. I have to say it surprised me a little. And then I spoke to a lot of Swedes, and I met some descendants of the Walloons. And that's when I really became aware of the phenomenon. It wasn't just an old migration story. It's a real topic within society. And in my opinion, it can be used as a lever for economic and cultural action.

That must make your mission all the more important...

It's true that when I was working in Asia, mentioning the word "Wallonia" didn't open doors in the same way! Here, the region has value. It's truly unique. And I'm committed to passing on this Swedish enthusiasm for the Walloons to the Walloons.

How? Through history lessons taught in our schools?

Let's just say that I hope the project I'm working on will lead Wallonia-Brussels to think along those lines, since they organise what's taught in schools. It really would be great to share this knowledge. Unfortunately, we have very little material in French, so we need to translate Swedish archives and books. And the sooner, the better. Because this past is something to be proud of. Say goodbye to the inferiority complex. Here, people's eyes light up if you're of Walloon origin! It's as glamorous as the Vikings!

There really is a lot of work to be done to improve the image...

Absolutely. The Marshall Plan also marked a turning point for me in Wallonia's self-image and its redevelopment in the early 2000s... Because we're still expecting Wallonia's financial autonomy from Flanders. There'll be further negotiations in 2024, and for them to be effective, it could be useful to rediscover this past and demonstrate our prosperity. Wallonia's image in Flanders is enough to make you cry. And I say that because I studied there and speak the language very well. I read some very harsh articles in the press, very often focusing on the negative. Now, with this story of Walloons in Sweden, we're sharing a narrative of something other than the endless tales of Wallonia in decline. There's a sense of pride that I like.

It's amazing that Swedes today still live with these memories from four hundred years ago...

Yes, but that's easily explained. During a metallurgy mission on metal recycling and decarbonisation, someone once showed me the Swedish prosperity curve. And on there, you could clearly see an acceleration from the time when the Walloons arrived. The Swedes are simply grateful. They live with this heritage every day.

And is Wallonia still attractive to Sweden today?

Yes, we're one step ahead in certain sectors. We've manufactured some vaccines that have been used there. We are also at the forefront of aeronautics and metal recycling. In Liège, in fact, we've developed an automatic sorting line for metal waste. That's no mean feat. And it shows that Sweden also has some things to learn from us on these issues. We're able to invent, inspire and collaborate. It's very motivating. But even so, Sweden still ranks second on the podium of the most innovative countries.

So the Walloons of Sweden aren't just ancient history?

No, otherwise I'd lose a significant portion of my work. They're still our tenth largest customer, and we still have some important ties. China is just behind, so that just goes to show... But I think we could deepen our cultural and even touristic links even further. The Walloon villages of Uppsala County should be recognised as Unesco heritage sites. They're unique. It's almost like a world heritage site. So we're going to do everything we can to highlight them and give them the funding they need to get back to their former glory.

Any last words? An anecdote to share?

Yes, yesterday a Swede handed me his business card and it had the Walloon Cockerel on it! I've never seen that anywhere. You can maybe see it in Wisconsin, in that famous Walloon village where traditions still live on. But I doubt it. What goes on here is truly unique!

Key facts and figures

- Around 5,000 Walloons arrived in Sweden in the 1620s.

- There are estimated to be between 800,000 and 1,000,000 Swedes of Walloon descent, accounting for around one tenth of the population.

- Sweden is now Wallonia's 10th largest customer.

- There are around 600 surnames of Walloon origin in Sweden.

- Until the 1920s, 23 bruks (Walloon ironwork villages) were producing iron bars from iron ore extracted from the Dannemora mine (in Uppsala County).

Did you know?

- In the 1620s, Wallonia was part of the Spanish Netherlands, ruled by Philip IV of Spain.

- Many of the Walloons who emigrated to Sweden came from the Liège region, Namur (Yvoir and Walcourt) and the Franchimont area (Chimay and Durbuy).

- The Walloon language was spoken in some parts of Sweden until the 19th century!

By Nadia Salmi

This article comes from the W+B Magazine n°161.